In part 1 and 2 of this article, we saw the unprecedented dislocations in ETF discounts and looked at the basics of ETF premiums and discounts. In this part, we will look at some examples of premiums and discounts at different scenarios and discuss how investors can monitor and manage premiums and discounts?

Examples of Persistent Premiums and Discounts

Of the 645 ETFs included in the sample I've referenced above, those that have exhibited the largest and most persistent premiums and discounts share some common characteristics. Of the 20 funds that had the largest median premium or discount during the past decade, 12 were international- or global-equity funds. Some or all of the stocks in these funds' portfolios trade on exchanges outside the United States, and their home exchanges' trading hours may have little or no overlap with U.S. trading hours. During these nonoverlapping hours, there is no real-time price information flowing from their constituent securities' home markets. In these windows, the funds effectively serve as "price discovery" vehicles, with buyers and sellers agreeing on fair values for a basket of stocks or bonds that may not be currently changing hands in their local markets. Thus, these premiums and discounts are part of the normal course of business in those cases where trading of an ETF's shares and trading of its portfolio holdings are out of sync.

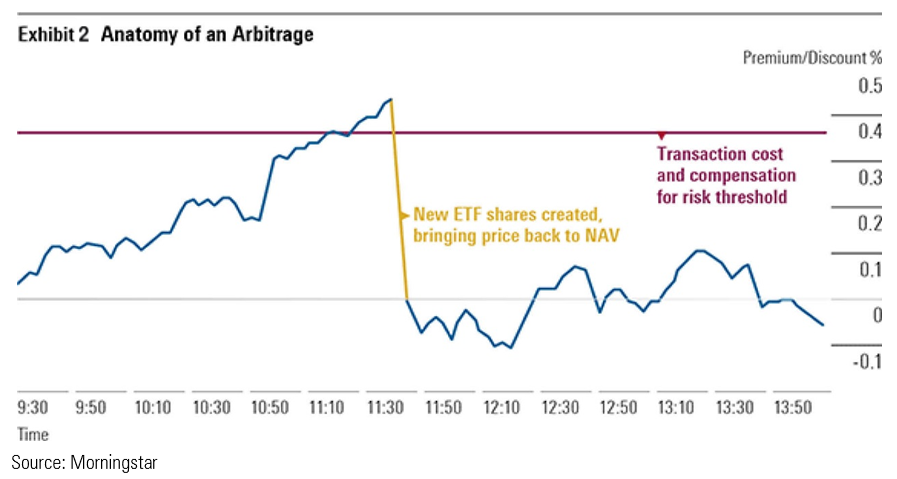

Bond ETFs represented seven of the remaining eight ETFs from the 20 that had the largest median premium or discount in the past decade. Premiums and discounts for bond ETFs are typically driven by 1) differences in the way bonds and the ETFs that hold them are priced and 2) costs. For example, at the end of a trading day, a bond ETF will be priced at the midpoint of the prevailing best bid and offer for its shares. However, its NAV will typically be calculated using the bid price for the fund's bonds. The end result is an apparent premium (that is, the ETF shares will be priced higher than NAV). Costs are also a factor. A fund's premium or discount will have to be sufficiently large to give an AP incentive to step in and exploit the arbitrage opportunity--as represented by the transaction cost and compensation for risk threshold in Exhibit 2. These costs, and hence this threshold, are typically far greater in the bond market, which is inherently less liquid than the market for stocks.

Examples of Episodic Premiums and Discounts

The episode we've seen in recent weeks is unique as measured by the magnitude of dislocations we've seen--which are without precedent. But there have been previous instances where ETFs' premiums or discounts have flared. No different than what we've seen more recently, these have typically been driven by dislocations in the market for ETFs' constituent securities.

For example, in the darkest days of the 2008-09 market meltdown, premiums for some fixed-income ETFs showed some staying power. During this period, some fixed-income ETFs became a source of liquidity for holders of these funds' underlying securities, who had almost no way to sell individual bonds on the market. For example, based on daily data collected by Morningstar, iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF (LQD) traded at a persistent premium to NAV for the period spanning from Lehman Brothers' bankruptcy in September 2008 through early 2009. During this span, the average daily premium was 2.3%.

On Aug. 24, 2015, many ETFs briefly traded at substantial discounts to their true value. An early-morning sell-off tripped circuit breakers that temporarily suspended trading in a number of stocks and, as a result, many ETFs that held those same stocks. Some investors fell victim to this downdraft, having placed trailing stop-loss orders in these funds' shares that became market orders at precisely the wrong time. Others were able to capitalize on this situation, placing buy orders for baskets of blue-chip stocks at bargain-basement prices. Episodes like these underscore the importance of assessing market conditions prior to trading ETF shares and practicing safe trading.

How Can Investors Monitor and Manage Premiums and Discounts?

There is nothing investors can do to directly manage the inevitable premiums and discounts to NAV that exist in the ETF market. Fortunately, these discrepancies tend to be fairly small and fleeting, thanks to the profit-seeking behavior of fiercely competitive market makers, so this should not be a major concern for most long-term investors.

However, when trading ETF shares, it is worth checking whether your buying or selling price is close to its iNAV. But not all brokerages in U.S. make this information available.

While iNAV is a useful touchstone, the prevailing market price is often the best indicator of a fund's going value. At any given time, market makers and other investors place their bid and ask prices on either side of their estimate of an ETF's fair value. If the bid and ask quotes are only a penny or two apart, the midpoint of the two numbers is probably an even better approximation of the NAV at that time. This is because supercompetitive market makers are leveraging their own proprietary pricing models to assess ETFs' fair values at hyperspeed during the course of the trading day in an effort to maintain their "edge" versus their competitors. Also, iNAV isn't as useful for bond funds or portfolios containing international securities, as their prices are likely stale. The SEC recently acknowledged this in its new ETF rule and no longer requires issuers to hire a third party to calculate and disseminate the value on their behalf.

Ultimately, the best way to protect oneself from these dislocations is to avoid trading during these episodes where ETF prices disconnect from their NAV.

But if you must trade, practice safe trading. In all cases, using limit orders is good practice. Limit orders will ensure favorable execution from a price perspective. A buy limit order will fetch the buyer a price less than or equal to the limit price, while a sell limit order will transact at a price greater than or equal to the limit price. What is the potential cost of using limit orders? Time and incomplete execution. That is, it may take longer for a limit order to be filled than a market order, and when that time comes it might not be completely filled. These costs need to be weighed against the cost of being exploited by an opportunistic market maker looking to pick off market orders.

And for those investors who can't or don't care to get comfortable with all the above, there is an expansive menu of index mutual funds to choose from that will guarantee your orders are executed at NAV.

.png)